Interactive Timeline

The groundbreaking ceremony for the Central Pacific Railroad is held on January 8, 1863.

The Big Four: Leland Stanford, Charles Crocker, Mark Hopkins and Collis P. Huntington, along with engineer Theodore Judah, gathered with local citizens on January 8, 1863, to break ground for the new Central Pacific Railroad. Though some road beds were graded, problems with raising money, finding laborers, and disputes among the partners delayed the actual construction until late October. Judah, the driving force behind the project, did not see the first rail laid, having left for New York to attempt to raise funds to seize control of the project from the Big Four. While en route, Judah contracted yellow fever in Panama and died one week later in New York. Learn more about Judah and the Big Four

Image source: Kraus, George. High Road to Promontory. Palo Alto, Calif: American West Pub. Co., 1969, p. 67.

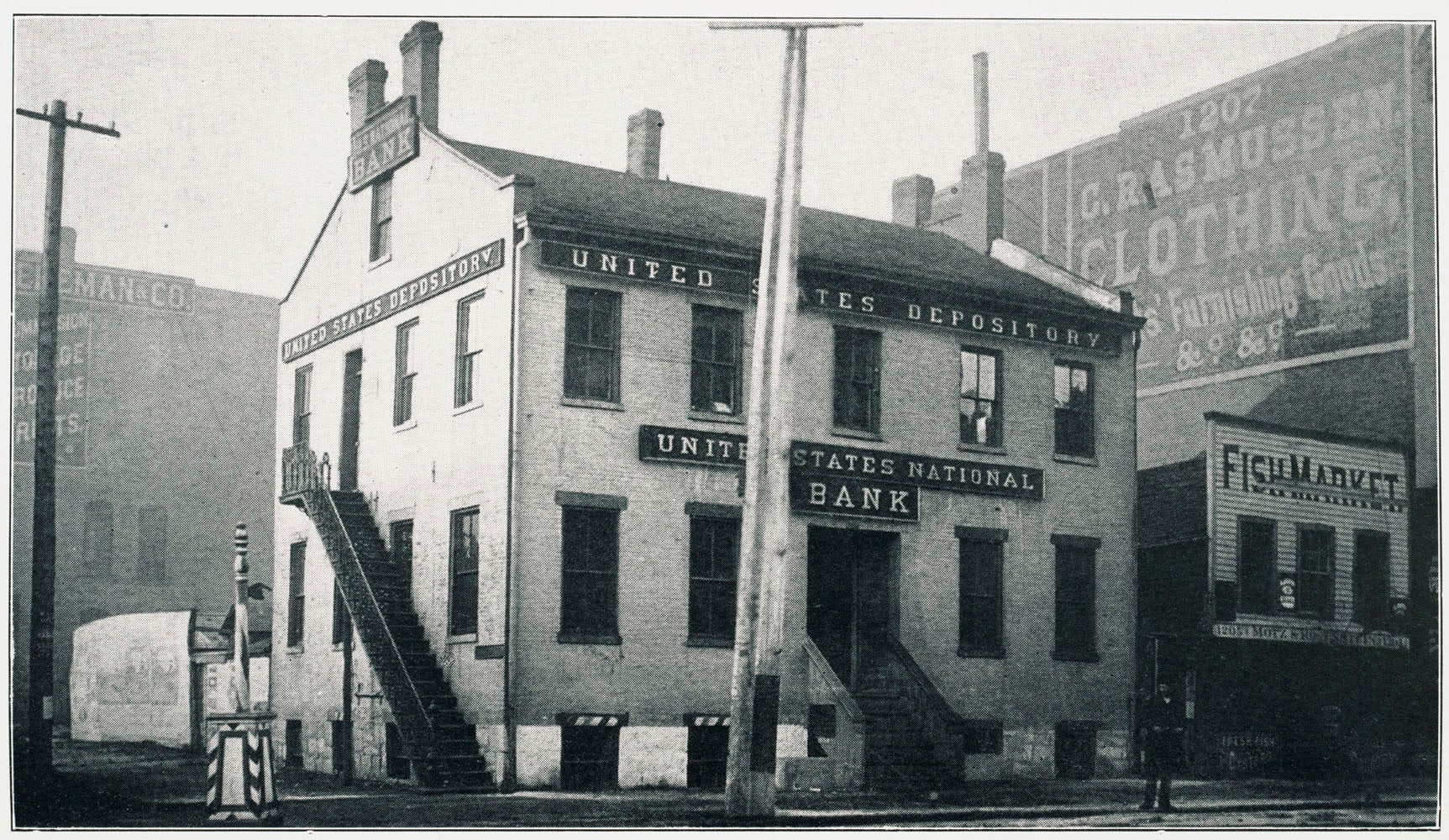

Omaha, Nebraska The Union Pacific heads west, laying the first rails on July 10, 1865.

Though Abraham Lincoln approved Grenville Dodge's recommendation of Council Bluffs, Iowa, as the eastern terminus of the Transcontinental Railroad, the practical starting point was across the Missouri river in Omaha. A bridge across the river built in 1873 would later link the two cities. As the Union Pacific drove the first spike in Omaha, the Central Pacific rails had reached 50 miles west of Sacramento.

Image source: Dodge, Grenville M. How We Built the Union Pacific Railway and Other Railway Papers and Addresses. Iowa: Monarch Printing Co., 1866 p. 127.

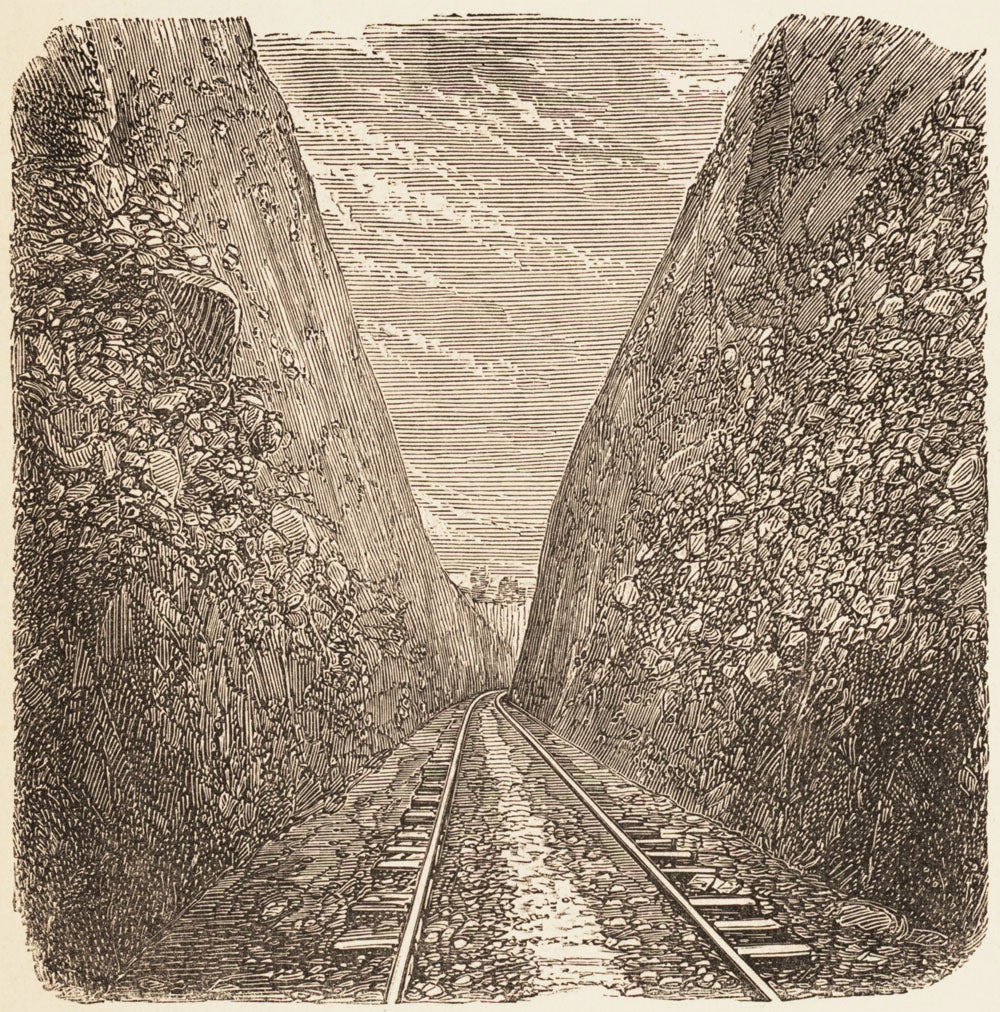

At Bloomer Cut, which took months to complete, workers blasted through solid rock to excavate a steep v-shaped cut sixty-three feet deep and eight hundred feet long.

Many cuts and fills were required to build the railroad. Workers blasted through rock in areas where the grade was too steep to lay track. The debris from blasting was hauled out with small horse carts, and in most cases, taken to the nearest fill, that is, areas where the road bed needed to be elevated. At times, more than 500 kegs of powder a day were used in blasting projects in the mountains. Learn more about explosives

Image source: Engineering (London, England). Vol. 4, London: Office for Advertisements and Publication, 2 Aug. 1867, pp. 88-89.

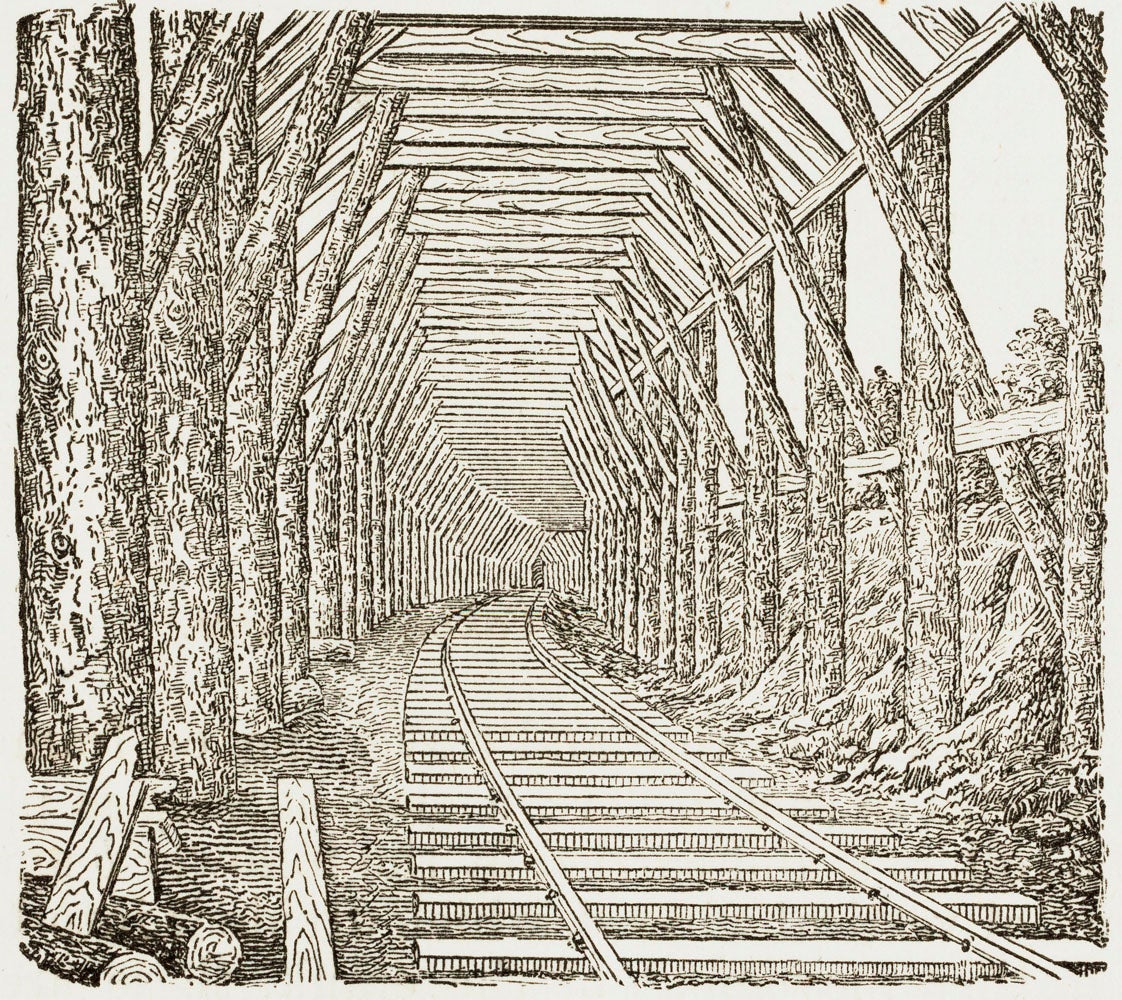

The 44 snow storms in the winter of 1866-1867 dumped almost 45 feet of snow in the Sierras. So that work can continue in the Sierras throughout the winter months, snow sheds were built over the tracks.

The fierce snow storms and avalanches killed men and made it next to impossible to move necessary equipment and supplies to the workers. Neither snow plows nor armies of digging teams could keep the tracks clear. Tunnels were dug under the snow to move workers and supplies, and in some cases served as housing for the workers. Leland Stanford came to the unpleasant realization that snow sheds would have to be built to cover the tracks in certain areas. The cost was enormous, but they had no choice if they had any hope of competing with the Union Pacific builders. The longest shed stretched 29 miles. Eventually, snow sheds covered 37 miles of track. Learn more about snow sheds

Image source: Knight, Edward H. Knight’s American Mechanical Dictionary. Vol. 3, New York: J.B. Ford and Company, 1874, pp. 2231, fig. 5257.

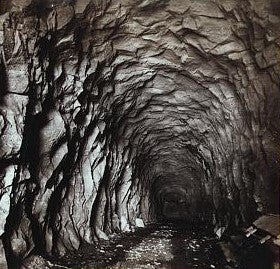

The Central Pacific digs the highest tunnel on the line at 7,017 feet above sea level.

The Central Pacific Railway's Tunnel No. 6, the Summit Tunnel, dug through 1,659 feet of granite in the Sierra Nevada's' Donner Pass, was the longest and highest tunnel on the line. Initially, crews excavating toward one another from the outer termini with black powder made insufficient speed, averaging only a foot or so per day. In August of 1866 workers dug a shaft down the center of the tunnel and began to dig and blast their way outward on two additional faces. Crews, made up primarily of Chinese laborers, worked in 8-hour shifts around the clock, living and working in crowded quarters wrested from the rock and snow. Introduced early in 1867, nitroglycerin mixed on site increased the pace of excavation in the headings from a daily average of 1.18 feet to 1.82 feet, and the tunnel was completed in November of that year. Learn more about explosives

Image source: Hart, Alfred A. Summit tunnel, before completion. Western summit, altitude 7,042 feet. 1865. Photograph. Library of Congress.

By April 15, 1868, the Union Pacific tracks had reached Sherman Summit, at 8,242 feet, a new record for the highest railroad tracks anywhere in the world.

Grenville Dodge decided a direct route through Wyoming's Black Hills over Sherman Pass was not only feasible but would shorten the track by 40 miles. The grade was not too steep and the lay of the land required curves of only six degrees, which was easily managed. Dodge named the summit after his old friend and former Civil War general William T. Sherman. Though snow falls at Sherman were not heavy, the unremitting wind created huge drifts, which required building some snow sheds and snow fences along the way.

Image source: Sherman Station, summit of Laramie range. Albany County, Wyoming. 1869. National Archives at College Park - Still Pictures.

On April 28, 1869, shortly before the Transcontinental Railroad was completed, the Central Pacific crew laid an astonishing ten miles of track in one day.

As the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific crews drew closer together in western Utah, their rivalry intensified. After the Union Pacific broke the record of six miles of track laid in one day, the Central laid seven miles. The Union, by working from three in the morning until midnight, laid seven and a half miles in a day. The Central Pacific crew replied with the vow to lay ten miles in one day. After working out a carefully organized strategy, the crew started at seven in the morning and finished the ten miles of track by seven that evening.

Image source: Cooley, Thomas McIntyre, and Thomas Curtis Clarke. The American Railway; Its Construction, Development, Management, and Appliances. New York: C. Scribner’s sons, 1889, p. 41.

The ceremonial golden spike is driven into the last rail of the completed Transcontinental Railroad on May 10, 1869.

As the Union Pacific and Central Pacific locomotives met nose to nose and the last spike was driven, the telegraph message "Done!" was sent across the land. The following day the New York Times reported that the city had been filled with the "booming of cannon, peals from Trinity chimes, and general rejoicing over the completion of the great enterprise. In the success of which not only this country, but the whole civilized world, is directly interested." In a relatively short time, the journey across the country had been reduced from six months to four days.

Image source: Sabin, Edwin L. Building the Pacific Railway. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1919, pp. 226-227.

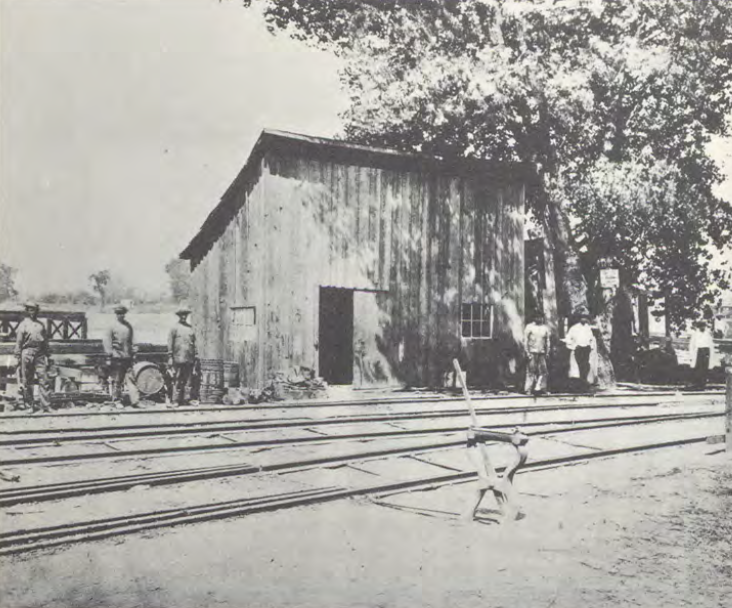

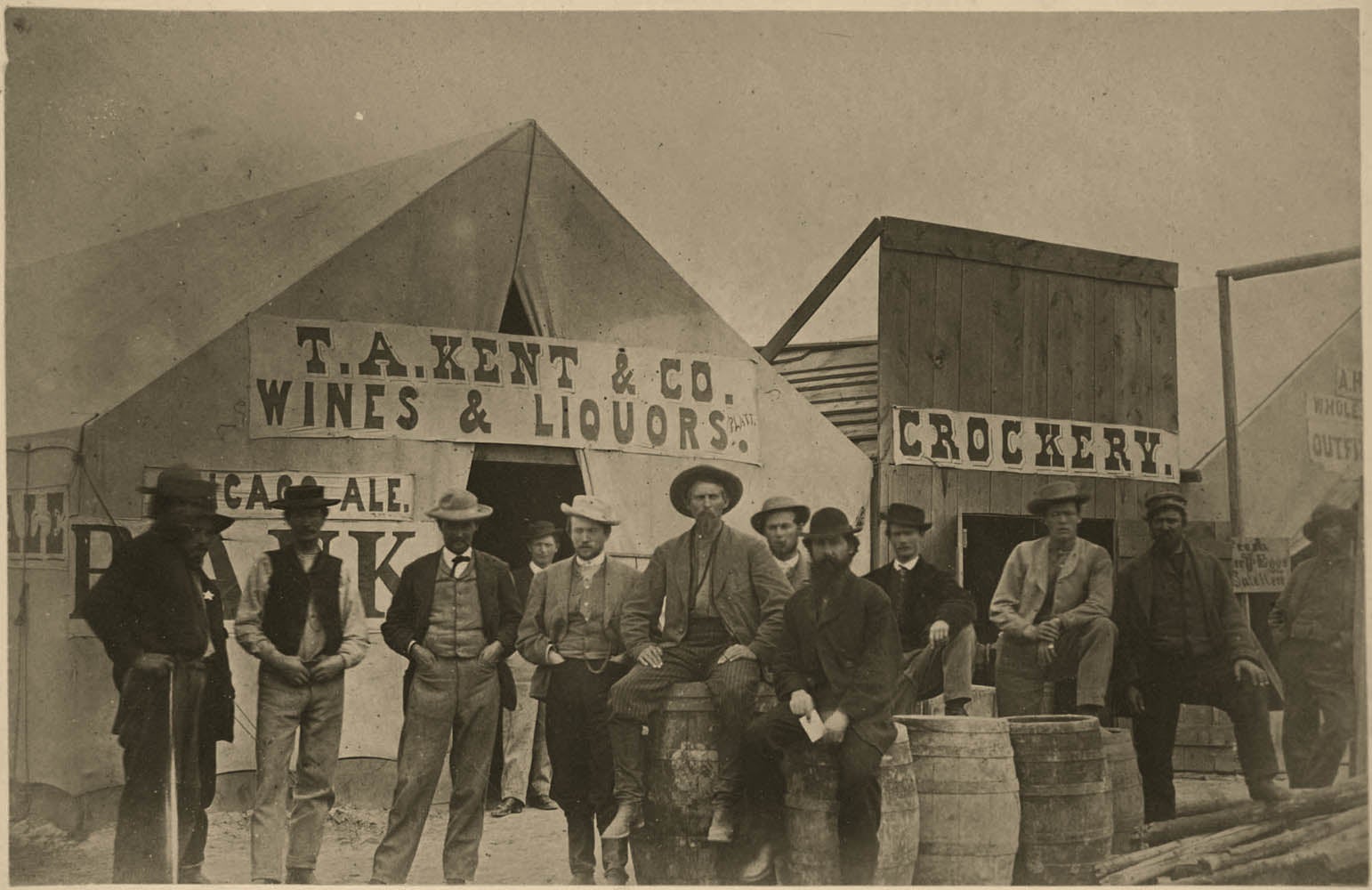

As the Union Pacific railroad moved west, towns sprang up at the end of the track. Known as Hell on Wheels towns, the collection of hastily assembled gambling dens, music halls, saloons, hotels, and houses of ill repute moved along with the railroad.

Travelling in the late 1860s, Samuel Bowles wrote that one Hell-on-Wheels town Benton, Wyoming, consisted of "canvas tents, plain board shanties, and turf-hovels." The town of 3,000 only existed for three months, but had 25 saloons and 5 dancehalls. About 100 people were killed in gunfights. Bowles described it as "by day disgusting, by night dangerous; almost everybody dirty, many filthy, and with the marks of lowest vice; averaging a murder a day; gambling and drinking, hurdy-gurdy dancing and the vilest of sexual commerce, the chief business and pastime of the hours." The proprietors of fly-by-night businesses took full advantage of young men with money in their pockets and few respectable places to spend it. As the railhead moved west, most of the Hell on Wheels towns followed, but some, like Cheyenne, Wyoming, remained, becoming established communities that no longer tolerated the gambling, drinking, and killing. Learn more about Hell-on-Wheels towns

Image source: Hull, Arundel C. Jack Morrow at Benton, Wyo. Terr. 1868. Photograph. Denver Public Library Special Collections, [Z-5803].

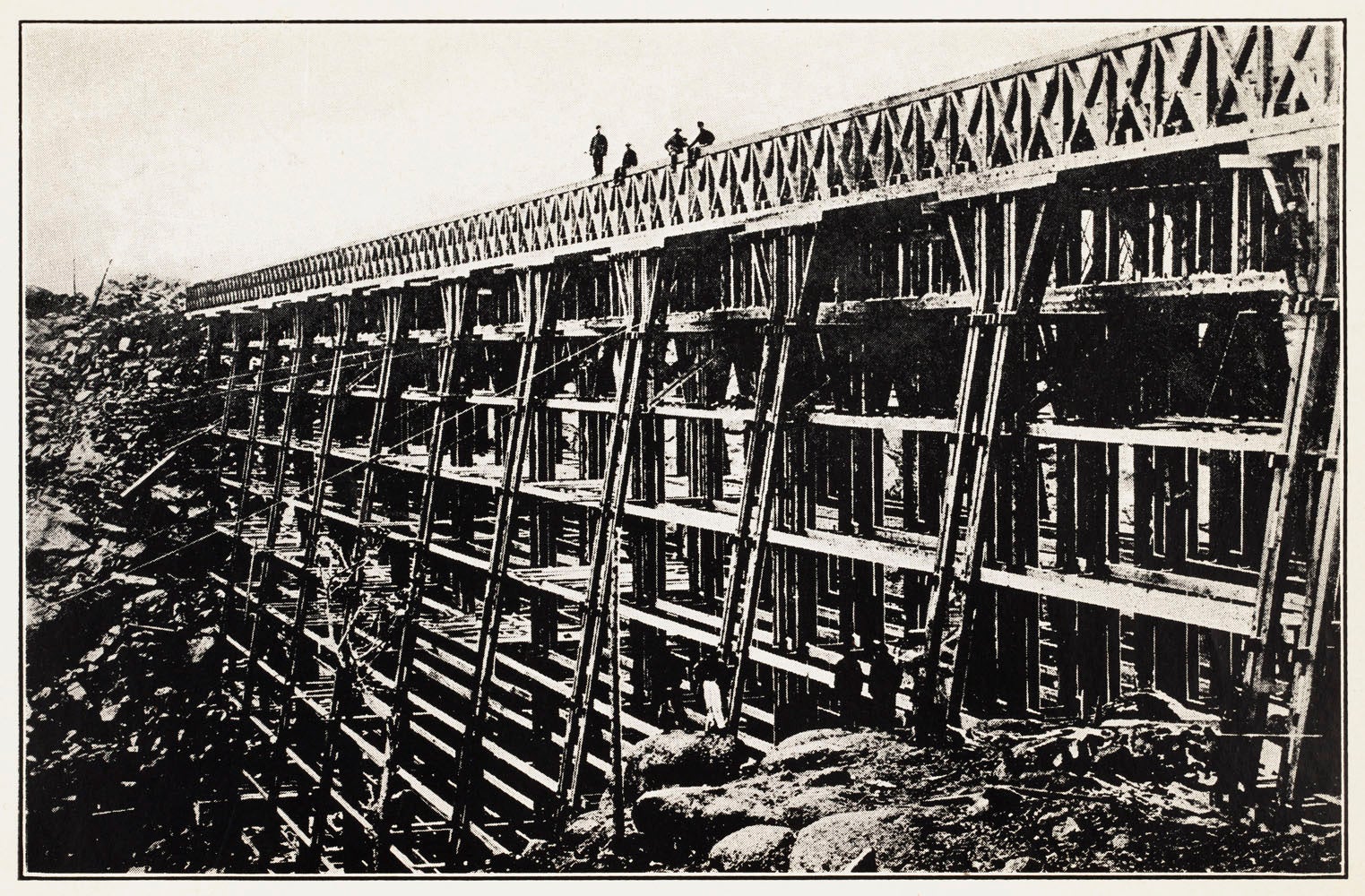

Dale Creek in Wyoming's Black Hills was a tiny little stream but ran through a deep gorge. Crossing it would require building a trestle bridge 126 feet high and 700 feet long.

Dale Creek Bridge was built entirely of wood from pieces fashioned in Chicago and shipped by rail to the railhead. The bridge was wobbly in the strong Wyoming winds and nearly collapsed during a storm when half finished. Engineers were understandably apprehensive when crossing it and adhered to the recommended speed of 4 miles per hour. In 1876, the wooden trusses were replaced by an iron bridge. Learn more about bridges and tunnels

Image source: Trottman, Nelson. History of the Union Pacific. New York: The Ronald press company, 1923, frontispiece.